|

(English translation below) Ek luister gisteraand na Ernst Roets se gesprek met Tucker Carlson.

Hy vertel die Afrikaner se storie van vervolging in Europa, die skepe Kaap toe, die Groot Trek weg van die Kaap-kolonie af, die veldslae met die Zulus, die oorloë met die Engelse, die konsentrasiekampe. Apartheid. 1994. Die ANC-regering se wanbestuur, korrupsie en ras-beheptheid. Die saak vir self-beskikking. Dis die storie van 'n groep mense se stryd om oorlewing. Ten spyte van terugslae en struikelblokke. Dikwels in isolasie. Dis 'n storie van planmaak. Van vasbyt. Van geloof. Maar dis ook 'n storie van "ons sal self." En soos alles, het hierdie storie ook sy skadukant. Want "ons sal self" sê iets van om in die steek gelaat te wees en op mensself aangewese te wees. Iets van 'n onvoldoende en bedreigende konteks (Europa, die Kaap-kolonie, die konsentrasiekampe, die ANC-regering se beleidsraamwerk en vervallende instellings, plaasaanvalle) waarvan weggevlug moet word. Of teen geveg moet word. En niemand wat hierdie kontekste bestudeer sal stry dat dit wel onvoldoende en inderdaad bedreigend was, en is, nie. My kinders moet ook hoor as hulle nie wit was nie sou hulle beurse kon kry. My swaer is ook 'n boer wat teen veediefstal en onteiening en plaasaanvalle moet sterkstaan. Ekself 'n konsultant wat telkens moet hoor jammer, jy's 'n wit man. Tog wil ek probeer om 'n alternatiewe manier van sin-maak en optree voor te stel. Sonder om die erns van ons huidige situasie te minimaliseer. Hiervoor wil ek leen by drie psigoanaliste: Melanie Klein, Wilfred Bion en Vamik Volkan. Melanie Klein, psigoanalis van die 1920's - 60's, het geskryf van die breedweg twee tipes sielkundige posisies waartussen ons onsself dag-tot-dag bevind. Die een punt van die kontinuum het sy die verdelende vrees-posisie genoem, en die ander punt die verdraagsame integrasie-posisie. (In Engels, die paranoid-schizoid position and depressive position.) Tot die mate waartoe mens oorweldig voel deur angs, neig mens om nader aan die verdelende vrees-posisie te beweeg, en tot die mate waartoe mens se angs onder beheer gehou kan word, raak dit moontlik om na die verdraagsame integrasie-posisie te beweeg. In eersgenoemde posisie, is die onbewuste verdedigingsmeganisme wat mens gebruik om tydelike verligting te bring, die sielkundige skeiding tussen "goed" en "sleg". Dinge word in binêre goed-sleg kategorieë verdeel. Dit maak die oorweldigende situasie eenvoudiger, meer draaglik, en bring dus tydelike verligting. Tydelik, omdat die oorvereenvoudiging tot goed-sleg, noodwendig nuanse, en dus 'n deel van realiteit, laat verlore gaan, so die oplossings wat vanuit hierdie gedagte-toestand gebore word, hou net só lank totdat realiteit mens inhaal, en mens van voor af moet begin, gewoonlik in 'n nuwe, erger-wordende siklus. Dink aan ons/hulle gesprekke. Ons is goed, hulle is sleg. Hiervan is oorlog 'n uitstekende voorbeeld. Die fantasie is dat, indien mens van die "hulle" ontslae kan raak, als goed sal wees, want die "sleg" is dan saam met die "hulle" daarmee heen. In rassisme, byvoorbeeld, het witmense swartmense tydens Apartheid as "sleg" of "minderwaardig" gesien, en hulleself as "goed" of "meerderwaardig", en daarvolgens opgetree. Soos Roets in sy gesprek met Carlson aangedui het, neem die Azaniese kritiese teorie weer die teenoorgestelde standpunt in: witmense het nie ubuntu nie en is dus sleg, swartmense het ubuntu en is dus goed. Die optredes wat hieruit volg word dan daarvolgens goedgepraat. In beide gevalle bly die onderliggende patroon van 'n vreesgedrewe verdeling tussen ekstreme egter instandgehou, en geen volhoubare oplossing kan gebore word nie. Die verdraagsame integrasie-posisie, daarenteen, verteenwoordig 'n denkruimte en gemoedstoestand wat bereid en instaat is om beide die goed en sleg en al die nuanse tussen-in, te hou. Daarmee te sit. Te verwerk. En dan oplossings te soek wat kan werk - vir almal. In Engels word dit die depressive position genoem, omdat die erkenning van mens se eie "goed" en "sleg" mens nie juis opgewonde maak nie. Dit laat mens met 'n realisme van aanvaarding van die onvolmaaktheid van mensself, mens se situasie, die ander mense waarmee mens moet saamleef, en ons almal se gebrekkige vermoë om wel iets werkbaars daar te stel. Wilfred Bion, psigoanalis van die 1940's tot 1970's, het Klein se idees verder gevoer en op groepsgedrag toegepas. Hy het gewys hoe groepe wat hulleself in die verdelende vrees-posisie bevind, geneig is om op die basiese aanname van veg-of-vlug te opereer. Menende die groep se angsvlakke kan nie intoomgehou en verwerk word nie, die skeiding tussen "goed" en "sleg", en die projeksie van die "sleg" op die "ander", kry die oorhand, en die gevolglike ervaring van gevaar en bedreiging noop die groep om te wil vlug uit die situasie, of die situasie of die "vyand" te wil beveg. In teenstelling hiermee het Bion die "werkgroep"-mentaliteit beskryf, waar groepe instaat is om die onsekerheid en kompleksiteit van oënskynlik onversoenbare teenoorgesteldes te kan hou en deurdink, en die moeilike emosies wat hiermee gepaardgaan, te kan deurpraat, eerder as om daardeur meegesleur te word. Vamik Volkan, psigiater en psigoanalis wat sedert die 1960's die psigodinamika van groot groepe, soos volke en nasies beskryf het, het 'n addisionele dimensie tot ons verstaan van groepsgedrag gevoeg, en dit is die idee dat groot groepe (soos volke, nasies, politieke partye of organisasies) wat nie hulle trauma uit die verlede, insluitend hulle oorsprongs-trauma, kan verwerk of transformeer nie, die gevaar loop om dit te herhaal, in erger-wordende siklusse, oor die verloop van tyd. En trans-formasie is nie dieselfde as revolusie nie. Revolusie beteken die wiel draai en draai. Wie bo was is nou onder en wie onder was is nou bo. Maar die onderliggende dinamika bly dieselfde. Transformasie beteken die onderliggende dinamika, sê-nou maar rassisme, word ten diepste en in wese verander en ongedaan gemaak, en nie bloot van wit-swart na swart-wit omgeruil nie. Terug na die Afrikaner-afvaardiging in Amerika. Daar is dus 'n ander manier om met die huidige situasie in Suid-Afrika om te gaan, as om dit in die howe of agter 'n geweerloop, of via Amerikaanse sanksies, te beveg. Of om daarvoor te vlug deur emigrasie, semigrasie of self-beskikking vir kultuurgroepe. Die veg of vlug narratief is gebou op die vrees dat die institusionele ruimte waarbinne ons onsself bevind, nie ons behoeftes en vrese veilig sal kan aanspreek nie, en dat die enigste moontlike opsies tot respons is om te vlug, te verskans of te veg. "Ons sal self." Ons het gevlug uit Europa. Gevlug uit die Kaap-kolonie. Geveg teen die Zoeloes. Geveg teen die Engelse. Geveg teen en gevlug van die swart en die rooi gevaar deur die verdelings, verskansings en vergrype van apartheid. Die probleem is dat die auto-respons van die een waarop ek my goed-sleg verdeling, en dus my gevolglike veg-vlug respons mik, is om op dieselfde golflengte van bewussyn te reageer. Dus as die manne gaan vuurmaak in Amerika, is die auto-respons van die ANC, wie in die eerste plek moet pa staan vir die verdelende wetsontwerpe, om hulle van hoogverraad aan te kla. Die saak raak dus warmer, die verdeling groter, en die kans vir verdraagsame integrasie van "goed" en "sleg" kleiner. Kan ons nie maar eerder praat en optree op maniere wat nie langs dieselfde veg-vlug kontoere loop nie? Hoe kan ons Melanie Klein se verdraagsame integrasie-posisie inneem? Of Bion se werk-groep mentaliteit? Of Volkan se transformasie van trauma-narratief? In teorie sal dit beteken om saam oplossings te soek. Te aanvaar ons is saam met mense van ander kleure en gelowe en kulture en filosofieë in hierdie ding. En ons moet saamwerk om die instellings, wat ons angs in toom kan hou en kan verwerk, en vooruitgang kan bring, te transformeer en sterk te maak. Want die disintegrasie van gesonde, werkende instellings, laat ons almal ontbloot staan en bedreig ons almal se voortbestaan. As dit nie vir Rassie Erasmus en die Springbokke was nie, sou die luide kritiek teen my skrywe nou gewees het dat ek idealisties en teoreties is, en dat daar 'n duisend en een redes is waarom mens nie met "hierdie mense" kan saamwerk nie, want "hulle" is sus en so en glo sus en so. Maar Rassie het, sonder om sy Afrikaner-identiteit prys te gee, dit reggekry om 'n instelling soos Springbokrugby, in murg en been te transformeer. (En transformeer beteken nie wat die BEE-argitekte dit gemaak het nie. Trans-formeer beteken om ten diepste 'n ander gees en vorm aan te neem.) En hy het dit gedoen nie deur die wetgewing oor kwotas in die howe te gaan beveg nie. Ook nie deur om by die Internasionale Rugbyraad te gaan vra vir ingryping nie. Of deur 'n alternatiewe, volkseie liga of -span te skep nie. Hy het bloot die ruimte geskep waarbinne hy en sy span openlik kon praat oor kwotas, rassisme, onderdrukking, vrese, wense, skaamte en woede. Groot emosionele gesprekke deur groot, gespierde manne van alle agtergronde en tradisionele kampe. 'n Ruimte waarbinne mense hulle vooroordele kan uitspreek, verdra en integreer. Nie bloot om te kan Kumbaya sing nie, maar om die wêreldbeker te wen. Twee keer en oppad na nommer drie. Ons Afrikaner voorouers sou tien teen een nie die psigoanaliste geraadpleeg het nie. Hulle sou na die Bybel gegaan het. Dalk moet ons ook maar. En stilstaan by die kern daarvan: die liefde. Want dit bedek alles, glo alles, hoop alles, verdra alles. (English translation assisted by ChatGPT) What Rassie understood, and we still must learn... I listened last night to Ernst Roets’ conversation with Tucker Carlson. He tells the story of the Afrikaner's persecution in Europe, the ships to the Cape, the Great Trek away from the Cape Colony, the battles with the Zulus, the wars with the English, the concentration camps. Apartheid. 1994. The ANC government’s mismanagement, corruption, and race obsession. The case for self-determination. It is the story of a people’s struggle for survival. Despite setbacks and obstacles. Often in isolation. It is a story of making do. Of perseverance. Of faith. But it is also a story of "we will do it ourselves." And like everything, this story also has its shadow side. Because "we will do it ourselves" says something about being abandoned and having to rely on oneself. Something about an insufficient and threatening context (Europe, the Cape Colony, the concentration camps, the ANC government’s policy framework and collapsing institutions, farm attacks) from which one must flee. Or against which one must fight. And no one who studies these contexts will argue that it was, and is, indeed insufficient and threatening. My children must also hear that if they were not white, they would be able to get scholarships. My brother-in-law is also a farmer who must stand strong against livestock theft, expropriation, and farm attacks. I myself am a consultant who repeatedly has to hear sorry you're a white man. Still I want to try to propose an alternative way of making sense and responding. Without minimizing the seriousness of our current situation. For this, I want to borrow from three psychoanalysts: Melanie Klein, Wilfred Bion, and Vamik Volkan. Melanie Klein, a psychoanalyst from the 1920s to the 1960s, wrote about the two broad types of psychological positions in which we find ourselves day to day. One end of the continuum she called the paranoid-schizoid position (fear-driven splitting), and the other end the depressive position (tolerant integration). To the extent that one feels overwhelmed by anxiety, one tends to move closer to the paranoid-schizoid position, and to the extent that one’s anxiety can be contained, it becomes possible to move towards the depressive position. In the first position, the unconscious defence mechanism that one uses to bring temporary relief is the psychological splitting between "good" and "bad." Things are divided into binary good-bad categories. This makes the overwhelming situation simpler, more bearable, and therefore brings temporary relief. Temporary, because the oversimplification of good-bad inevitably causes nuance, and therefore part of reality, to be lost, so the solutions born from this mindset last only until reality catches up, and one must start all over again, usually in a new, worsening cycle. Think of us/them conversations. We are good, they are bad. War is an excellent example of this. The fantasy is that, if one can get rid of the "them," everything will be fine, because the "bad" will be gone along with the "them." In racism, for example, white people saw black people during Apartheid as "bad" or "inferior," and saw themselves as "good" or "superior," and acted accordingly. As Roets pointed out in his conversation with Carlson, Azanian critical theory takes the opposite stance: white people do not have ubuntu and are therefore bad, black people have ubuntu and are therefore good. The actions that follow from this view are then justified. In both cases, however, the underlying pattern of a fear-driven division between extremes is maintained, and no sustainable solution can be born. The depressive position, on the other hand, represents a state of mind that is willing and able to hold both the good and bad and all the nuance in between. To sit with it. Tolerate it. Process it. And to then seek solutions that can work - for everyone. This is called the depressive position, because the recognition of one’s own "good" and "bad" does not exactly make one excited. It leaves one with a realism of accepting the imperfection of oneself, one’s situation, the other people one must live with, and our collective limited ability to establish something truly workable. Wilfred Bion, psychoanalyst from the 1940s to the 1970s, developed Klein’s ideas further and applied them to group behaviour. He showed how groups that find themselves in the paranoid-schizoid position tend to operate based on the basic assumption of fight-or-flight. Meaning that the group's anxiety levels cannot be contained and processed. The splitting between "good" and "bad," and the projection of the "bad" onto the "other," gets the upper hand, and the resulting experience of danger and threat compells the group to either flee from the situation or to fight the situation or the "enemy." In contrast to this, Bion described the "work group" mentality, where groups are able to hold and think through the uncertainty and complexity of seemingly irreconcilable opposites, and the difficult emotions that accompany them, can be discussed rather than reacted to. Vamik Volkan, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who has studied the psychodynamics of large groups, such as peoples and nations, since the 1960s, added an additional dimension to our understanding of group behaviour: Large groups (such as peoples, nations, political parties, or organizations) that cannot process or transform their past traumas, including their origin trauma, run the risk of repeating them in worsening cycles over time. And transformation is not the same as revolution. Revolution means the wheel turns and turns. Whoever was on top is now at the bottom, and whoever was at the bottom is now on top. But the underlying dynamic remains the same. Transformation means that the underlying dynamic - let’s say, racism - is fundamentally and essentially changed and undone, and not merely switched from white-black to black-white. Back to the Afrikaner delegation in America. There is thus another way to approach the current situation in South Africa, rather than fighting it in the courts, at gunpoint, or through American sanctions. Or fleeing through emigration, semigration, or self-determination for cultural groups. The fight-or-flight narrative is built on the fear that the institutional space in which we find ourselves cannot adequately contain our needs and anxieties, and that the only possible response is to flee, fortify, or fight. "We will do it ourselves." We fled from Europe. Fled from the Cape Colony. Fought against the Zulus. Fought against the English. Fought against and fled from the black and red danger through the divisions, entrenchments, and transgressions of Apartheid. The problem is that the auto-response of the one to whom I direct my good-bad split, and thus my resulting fight-flight response, is to react on the same level of consciousness. So, if the men go to stoke the fire in America, the auto-response of the ANC, who in the first place has to take responsibility for its divisive legislation, is to charge them with treason. The issue heats up, the division grows, and the chances for tolerant integration of "good" and "bad" get slimmer. Can we not rather speak and act in ways that do not follow the same fight-flight contours? How can we adopt Melanie Klein’s depressive position of tolerant integration? Or Bion’s work-group mentality? Or Volkan’s transformation of trauma narratives? In theory, this would mean seeking solutions together. Accepting that we are in this together, with people of different colours, religions, cultures, and philosophies. And that we must work together to transform and strengthen the institutions that can contain and process our anxiety and bring progress. Because the disintegration of healthy, functioning institutions leaves us all exposed and threatens our continued existence. If it weren’t for Rassie Erasmus and the Springboks, the loudest criticism against my writing right now would be that I am idealistic and theoretical - and that there are a thousand and one reasons why one cannot work with "these people," because "they" are this and that and believe this and that. But Rassie, without giving up his Afrikaner identity, succeeded in transforming an institution like Springbok rugby, right through to the bone. (And "transform" does not mean what the BEE architects have made it out to be. Transformation means to fundamentally take on a different spirit and form.) And he did not do it by fighting the quota laws in court. Nor by asking the International Rugby Board for intervention. Nor by creating an alternative, Afrikaner-only league or team. He simply created the space in which he and his team could openly talk about quotas, racism, oppression, fears, desires, shame, and anger. Deep emotional conversations among big, muscular men from all backgrounds and traditional camps. A space where people could express, tolerate and integrate their prejudices. Not just to sing Kumbaya, but to win the World Cup. Twice. And counting. Our Afrikaner ancestors would probably not have consulted the psychoanalysts. They would have turned to the Bible. Maybe we should too. And pause at its core message: love. Because it covers all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures (tolerates) all things.

0 Comments

It's now been six years since we started the first Consultancy Training Group in Pretoria, South Africa. Since then consultants, coaches and senior managers from South Africa, Zimbabwe, The Netherlands, India, Turkey, Israel, the UK and Germany have participated.

One thing that I have learnt, given the fact that I've been reading the material again and again before each session, is that there is no end to the learning. Each session is different. And the dreams, insights and challenges that people bring differ from session to session. Learning about and working with the unconscious dynamics affecting us at work is a path that can keep one fulfilled and busy for one's entire career. Plus you know that you are contributing to the life, creativity and success of the institutions that serve our economies and communities. A valuable endeavour indeed! I remember the review and application group.

It was in the second week of my first Leicester Conference, 2008. We were six in the group. Two presented the previous day: A woman from Sweden and another woman from Kuwait. That day, it was my turn, together with a man from the Netherlands. I presented some sort of mind map of the various roles I found myself in outside of the conference. The previous night I had worked into the morning hours to get it completed. There was my role as lecturer at the university, my part-time team building facilitator role, my previous HR role at a local bank, my role in a research team as well as my role in a local community project in Johannesburg. For each role I mapped out the significant authority figures involved, the tasks I were responsible for, the pressures. On this map I superimposed a map of my conference experiences until that point, complete with cross-references and colour codes. It was a masterpiece! We were sitting in a circle. The group hunched over the flipchart paper on the floor with my sticky-note mind map and arrows and colours. I spoke and pointed and explained. I wanted to show something of how much responsibility I was taking. How I was being pulled into different directions. But I also wanted them to see how good I was at this. That I got it. When I finished, I sat back in my chair, waiting for the consultant, a lovely bald man from Portugal, to speak. Ready to receive some praise for my hard work. He was sitting next to me. In silence, for a moment or two. Then, he looked straight at me, and asked: "May I ask you a question?" "Yes," I said. My heart rate picking up. "How many fathers do you have?" The question, like an arrow, pierced right through the noise and pretence. Bulls eye. "And what do you owe them?" Ouch. Another one. Deadly accurate. I looked around the room. Swallowed at the lump in my throat. A wetness in the corners of my eyes. I saw the empathy on the others' faces. Realised that they had seen exactly what the consultant saw. Somehow, that which I did not say, seeped so thoroughly through my presentation, that no-one could miss it. Except me. I had been so busy, the previous night and the years before that, trying to impress and work and satisfy, that I missed the obvious pattern running through more or less all my role-relationships: The unpleasable father-in-my-mind. Re-created. Again and again and again. In a never-ending series of attempts to finally please perfectly. What a liberation. To join the 2024 Leicester Conference, click here. It is now 16 years since that fortnight in England that changed everything.

I remember arriving there, in that typical ‘not-knowing-what-I-don’t-know’ certitude. Thinking the fact that I was a psychologist put me in a better position than the business executives around for what was lying ahead. I remember having tea with a group of people, who seemed more or less my age, just before the conference started. There was a guy from Singapore, one from Denmark, a woman from Romania and one from Lithuania. We were filled with butterflies, knowing that we were about to dive into an immersion that would change us. What I didn’t know, couldn’t have known, was just how profound this change would be. It was that first Leicester experience, in 2008, that kick-started my journey into myself and onto what would become an unbelievably fulfilling career. Like any life-changing adventure, there is only one way to make it happen: Decide that you want to go. Then figure out the practicalities. This year the conference will be in August, and I will be one of the consultants, working alongside some of the people whom I met during that 2008 conference. Get the 2024 Leicester Conference brochure here. We were living in Chicago. My wife was posted to the South African Consulate there, and I had to take care of our children (aged 6, 4, and 2), finish my dissertation, and teach. Additionally, I began psychoanalysis: four years, four days a week, on the couch. One day, my son fell ill and couldn't attend school, so I had to take him with me to my session.

We know that South African society is traumatized, that trauma shatters mind and society, and that unworked trauma repeats itself over generations. We also know that trauma impedes our ability to think together rationally and therefore we know that there is no way out of our current mess if we don't simultaneously deal with our collective underlying trauma.

What we don't know, is how to do this. South Africa is in trouble. Our society is traumatised and the trauma continues. Colonization, war, Apartheid and poverty, amongst other factors, have contributed to a historical cycle of perpetual trauma. Today, violent crime, rampant corruption, gender-based violence, drug abuse and unemployment are not only some of the manifestations of this ongoing trauma but are also continuing to keep the traumatic cycle in place.

One of our local schools regularly posts a new quote on their billboard. This week it reads: "Some people look for a beautiful place. Others make a place beautiful."

This made me think of our recent family road trip on South Africa's backroads. We travelled on gravel and pot-hole-riddled tar roads through towns such as Wolmaransstad, Schweizer-Reneke, Coligny, Jan Kempdorp and Prieska and Carnarvon. Forgotten towns on their last breath. Has it always been so hard for me to transition back into my work role after the summer holidays? Or is it more difficult this year?

Of course, being in a freelance leadership consulting role usually means that one's clients need a week or so to settle back into their own roles before seeking out coaching or consultation at the start of the new year. Meaning that the main activities constituting the consulting/coaching role (making appointments, seeing clients, keeping notes) only really start in the third or fourth week of January. Until then we are thus largely bereft of our usual role-activities as a bulwark against our own anxiety. This photo was taken 10 minutes before I got a puncture in the back tyre. I had just bought the bike in Riversdale and was on my way back to Pretoria. Suddenly the bike started to move under me as if I was riding through thick sand, which I wasn't. When I stopped to check and saw that the tyre was flat, I knew: everything has just changed. There was no way I was going to go all the way to Loxton as planned - depending on how quickly I could fix the tyre, of course.

These class notes may be valuable to anyone responsible for leading complex project teams. The notes form part of the module "Project Organisation" that I teach to Masters of Project Management (MPM) students in the Engineering Faculty at the University of Pretoria. The module looks at the unconscious dynamics affecting project teams as systems within a wider systemic context.  Photo by Jo Van de Kerkhove on Unsplash Photo by Jo Van de Kerkhove on Unsplash There is only one way in which one can understand anything about the teams you are part of, and that is to acknowledge that your team, like all other human systems (families, businesses, governments), is imperfect.

These class notes may be valuable to anyone responsible for leading complex project teams. The notes form part of the module "Project Organisation" that I teach to Masters of Project Management (MPM) students in the Engineering Faculty at the University of Pretoria. The module looks at the unconscious dynamics affecting project teams as systems within a wider systemic context. Introduction to Module

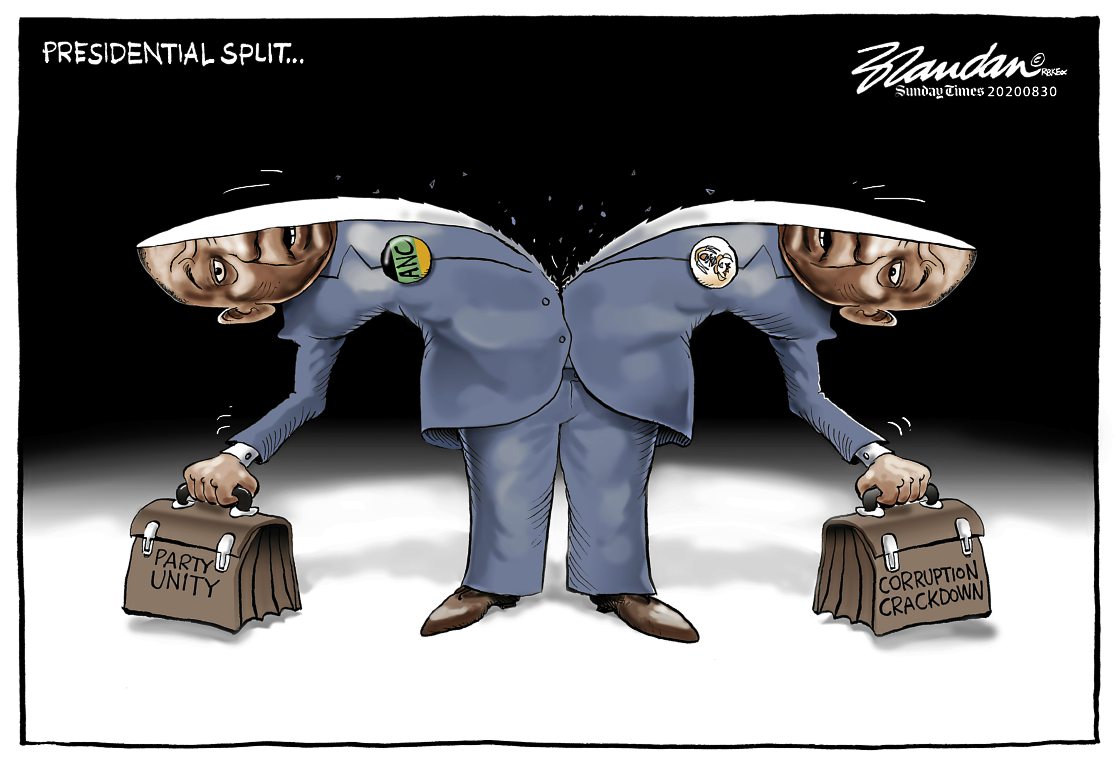

Managing projects is complex and requires a high degree of competence in a variety of disciplines. Although the project manager may not need to be an expert in any of the disciplines composing 'project management', he or she has to be good enough in each of them, plus be an expert in putting it all together. James Krantz* writes beautifully how important it is for leaders to have the courage to betray personal relationships and expectations when required. If you are the one in charge, you will sometimes have to make decisions that will upset some of your closest allies in order to do what is best for the team, business or country that you are leading. President Ramaphosa has started this process, but it is clear that it will not get any easier as the realisation sets in that corruption is systemic - meaning that it is impossible to root it out by only focusing on the individuals that get caught out.

A trend that I see emerging is that companies are increasingly introducing well-intended initiatives to encourage managers and staff to take care of themselves during these plagued times.

Of course, people should take breaks, manage their work/home boundaries, exercise, eat healthily, not drink too much alcohol and seek out professional counseling when their depression or anxiety is edging out of control. However, putting too much emphasis on self-care can be harmful if this is not mirrored by the organisation's own introspection and re-alignment. The only way in which we can really make sense of our teams and organisations is to view them as imperfect human systems. Not only are our current teams and organisations imperfect, but we all come from a history of belonging to and being formed by imperfect human systems.

By acknowledging this to ourselves and each other, we can stop pretending to be the perfect team or company. This means we can start becoming curious about the ways in which we are contributing to the imperfections, rather than being defensive and trying to blame others for things that go wrong. |

This blogThis blog serves as a journal of thoughts, reflections, opinions, case discussions and lecture notes that I have created as part of my work with clients, students and colleagues. Plus some stories of journeys to faraway places. Categories

All

AuthorRead more about me here. Contact me: [email protected] Archives

March 2025

|

Copyright Dr. Jean Henry Cooper

Contact me: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed